This Open Cabin Was Designed For Children

The fully detached home—with front and back patios—was built in 1872, and it’s still packed with period detail after a top to bottom revamp.

Location: 956 South Van Ness Avenue, San Francisco, California

Price: $4,495,000

Year Built: 1872

Architect: Edward Leodore Mayberry

Renovation Date: 2017

Renovation Architect: Paul Molina

Footprint: 5,158 square feet (4 bedrooms, 5.5 baths)

Lot Size: 0.1 Acres

From the Agent: “956 South Van Ness is a historic grand Italianate Victorian built in 1872 by noted architect Edward Leodore Mayberry. During an extensive two-year restoration/renovation in 2017, a thoughtful commitment was made to honor its history and artistic accents while upgrading the interior for modern living and a full upgrade in systems including the foundation, electrical, and plumbing. The main level is an entertainer’s dream with grand rooms (all w/soaring ceilings), a chef’s kitchen, and a sun-filled walkout garden. Upstairs are three bedrooms and three full bathrooms. The lower level was completely built out for additional living space (and bedroom) with a full bath (or a future unit with plumbing for a small kitchen). Additional features of this spectacular, fully detached home include a two-car side-by-side garage, an 800-bottle wine room, two laundry rooms, and abundant storage throughout.”

Open Homes Photography

The home’s stained glass was sourced from Cradle of the Sun, a local store.

Open Homes Photography

Open Homes Photography

See the full story on Dwell.com: Asking $4.5M, This Huge, Historic San Francisco Victorian Is a Rare Find

In my fight against infestation, I realized that no man is an island, least of all in the New York City rental market.

This is a story with a happy ending—community, hope, a deeper understanding of how we could live in the world—but a less serendipitous beginning. I was lying in bed, falling asleep, when I felt a tickle on my arm. I brushed it reflexively, expecting to feel nothing much, but instead I felt, curled up in my hand, squirming: a roach. Running across me. While I was supposed to be safe and sound in bed. The anguish.

The bug was not, unfortunately, a total surprise. Since I had moved into my grungy, downtown Manhattan fifth-floor walk-up in early 2021, I had been dealing with roaches. At first they were a novelty, a sort of quirky new scenario in my zany New York sitcom. I set traps, poisons, consulted my building’s exterminator. I assumed they’d be a passing crisis, forgotten tomorrow with the next episode’s adventures. When they endured, comedy turned to tragedy. The problem seeped into my self-image. Was this me? Was I the sort of person who had roaches in their apartment?

I had visions of Kafka’s The Metamorphosis and that clip of the woman on 1000-lb Sisters crying about people seeing roaches in videos of her home while a roach is climbing up the wall in the background. Roaches are a tough look to pull off. Other apartment issues can be fun, even vaguely glamorous in a tongue-in-cheek boho chic kind of way. “Oh, my hot water is out because my landlord can’t seem to fix the boiler”—it’s a problem out of La bohème, one that you might tell a friend before breaking out into an aria about being an artist seeking true love. But a bug problem feels personal, a supposed reflection of moral failure. In my mind, I had roaches because on some existential level I was doing something wrong.

At this point, I hear you whispering the same thing that I initially told myself: Move. Get out of there. Heal thyself in the sanatorium of a new home. The problem was that I was trapped by the New York City rental market.

I moved into my place in the depths of the pandemic, when people were leaving cities for big country homes or Florida or wherever else. New Yorkers were fleeing in droves, and the Manhattan market tanked. Landlords were offering deals: Three months free! $400 off your rent for six months! Fortunately, I had the advice of a friend who works in affordable housing, and I snatched one of the deals in a rent-stabilized apartment where the landlord wouldn’t be able to jack the rent back up when the crisis passed. I signed a lease for $1,600 per month for a one-and-a-half-bedroom in Little Italy. I knew that I’d never find something like that again, barring another world-stopping catastrophe.

So, I dug in and didn’t flee. But neither did the roaches. Eventually, I asked experts beyond the friendly man who came once a month to spray the building what I should do, but I only did that after I had tried to handle the problem on my own. As the experts later told me, I started going about it all wrong.

Initially, after doing a deep clean to make sure there were no hidden roach nests in the apartment, I set baited traps to kill whatever might be hiding, which Jesse Scaravella, owner of Evergreen Eco Pest Control, now tells me is a common mistake. “Everybody gets on the bait cycle,” he says. The problem with baited traps is that in addition to trapping roaches, they also attract them. “You’re kind of creating a beacon.” I was dealing with German cockroaches, which are smaller than the monstrous American cockroaches. Despite being larger, I learned that American cockroaches are less of a headache overall. In New York apartments, they’re usually lost wanderers coming up from sewers via pipes. They are big, but they are often solo travelers and are less likely to linger and infest than their smaller German counterparts. German roaches, once invited inside by bait or food crumbs, will lay eggs and reproduce, multiplying your problems. Because they’re so small, they can get in from small cracks or gaps around poorly sealed pipes, for instance, or even the gap beneath the door. Once inside, they look for moisture and food and can snuggle up in tight spots.

Roaches, I realize, are an architectural issue, and in an old claptrap like mine, the borders are weak.

“Cardboard is the enemy,” Scaravella tells me. “All those boxes are infamous for traveling roaches.” Collections of plastic bags, like the kind I used to keep under the sink, also create cozy breeding grounds for them.

Scaravella’s advice is to clean up food crumbs carefully and look for anywhere that moisture accumulates—maybe condensation on a cold pipe or in an appliance. Deal with that, and you will reduce what is attracting the bugs into your home. The next step is keeping them from getting in at all.

“The question is not about, Can you get rid of them?” Timothy Wong, the technical director at M&M Pest Control, tells me. “The question is, Can you prevent them from coming in?”

After pooh-poohing the other products I panic-bought to keep the bugs away, like essential oils or plug-in sonic repellers, Wong advises me on what exterminators call exclusion, or closing up your apartment so nothing unwanted can get in. “The best long-term solution is sealing up all the access points,” he says.

It’s easier said than done. After I start looking for ways in, I can’t stop finding them. My old tenement apartment, layered with various cheap renovations, is a nightmare. I discover a crack where the floor for some reason steps up, small holes around the showerhead, an eerie gap where a pipe runs through the ceiling into the great beyond. I caulk in a frenzy, and when the gaps are too wide, I roll out the duct tape. I develop a maniacal focus on recording where I see them to figure out how they get in, making spreadsheets of sightings. For the persistently difficult portal to hell apparently located in the cabinets beneath my kitchen sink, I bust out some double-sided carpet tape and line the front perimeter of the cabinets to create a barrier that catches any bugs trying to escape, trapping them until I pluck them out to their graves.

I make some progress, liberating the bathroom and bedroom, but I can’t seem to win the whole apartment. Roaches, I realize, are an architectural issue, and in an old claptrap like mine, the borders are weak.

“The problem is that in New York City, you’re not living in an apartment where you are the only caretaker,” Wong tells me. “You’re living with all these neighbors, and you have no idea what their sanitation or hygiene is like.”

No matter how clean I keep my place and how many cracks I fill, I can’t control what happens next door. This ends up being my final liability.

“That front door is always going to be subject to insects coming in,” Wong says, and he’s right in my case. It’s the one place where the roaches still made it inside, even after all of my efforts. It’s not possible, apparently, to seal myself off from the world around me. Who knows if one of my 20-or-so neighbors is hoarding old boxes or leaving food out overnight or being anything less than monomaniacal in their focus in combatting the roach scourge? Who around me is not part of the solution and is therefore part of the problem?

The more I chat with the people around me, though, the less I think that my neighbors are really the enemy. Many of us are in the same boat: We hate the bugs, but our rents are too good to let go of in a city so expensive. Rent stabilization has put us all in a battle together, and though I see us as a horde of tenants floundering in roach-infested waters, others envision more potential.

Cea Weaver, the director of New York activist group Housing Justice for All, tells me, “Rent stabilization…creates a political class of people who can act together.” Neighbors with trash aren’t the enemy; our crummy housing system is. Weaver gives me a quick history of rent stabilization and what it does. “The Emergency Tenant Protection Act, which is commonly known as rent stabilization, has been around since 1974,” she says, but over the following decades, the real estate industry successfully lobbied to get loopholes in the system that reduced the number of stabilized units in the city. A 2020 study from the New York City Rent Guidelines Board found that the city had lost about 145,000 rent stabilized units since 1994.

I’ve started to think of my roaches not as a personal flaw but as a defect in the country’s housing system.

In 2019, tenants groups like Housing Justice won big in the state legislature, which decided to strengthen rent stabilization in New York City and expand it to the rest of the state in what Weaver calls a “generational victory.” Now, Weaver calls rent stabilization “the gold standard when it comes to tenant protections, and it covers about forty percent of the rental housing stock in New York City.” As she explains it, the system essentially guarantees the right for tenants to renew their leases and limits the amount that rents can go up. Rent stabilization laws set up the Rent Guidelines Board, which meets annually to determine the most that stabilized rents can go up that year. During the peak pandemic years, the board said that stabilized rents couldn’t go up at all. Usually the amount is in the low single digits.

Weaver and Housing Justice are now trying to organize tenants into a political group that can advocate for better living conditions. The U.S. housing system has long privileged homeowners, offering them tax breaks and mortgage protections. Ownership is part of the American dream. But Weaver and I discuss how outdated that model is at a time when more and more people are giving up on the idea of ever buying a home, especially in New York City. “Stability and security is not something that can be reserved for people who own a home,” she says.

Rent stabilization is perhaps not the sexiest solution to the housing crisis, but, Weaver says, it’s one with the ability to help people across social spectrums. “One of the things that I think makes rent stabilization so special is how many different types of people have a stake in it succeeding,” she says. “It is for working class people. It’s for low-income people, it’s for middle-class people. Stabilization is for everybody.”

I’ve started to think of my roaches not as a personal flaw but as a defect in the country’s housing system that leaves so many people fending for themselves and fighting for whatever bits of shelter their landlords deign to provide. More cynically, I have thought of the roaches not as a bug but as a feature of my apartment, one that gets tenants with good deals to move out so the landlord can raise the rent.

I wish I could say I have drawn some wisdom from my roach experience, but the whole ordeal just illustrates to me how little wisdom there is in the American approach to housing overall. After talking to Weaver, I wondered if my time would be better spent petitioning my state senator for better housing policy instead of caulking some crevice for 30 minutes every week.

But then something wonderful happened, at least for me: Last summer, the roaches disappeared. I suspect it had less to do with my work and more to do with some light renovations done to the bakery next door and the stairwell of my building. Whatever, I’ll take the win. At this point, though, I can’t go back to naive optimism about my housing future. I’m sure it’s only a matter of time before I make some other concession to stay in my apartment. Already, my rent has crept up over the past few years, far faster than my salary has, thanks to our current mayor’s appointments to the rent stabilization board, who have voted to allow rents to rise. It may be time to take my battle outside of my home.

“The cost of living crisis is out of control, and we need a rent freeze,” Weaver says. Her goal faces some stiff headwinds: Andrew Cuomo is a leading candidate in this year’s mayoral election, and he has reportedly told real estate leaders that he regrets elements of the 2019 reforms bolstering rent stabilization, which he signed into law when he was governor. But other candidates, like Zohran Mamdani, have signed on to the idea.

Any long-term vermin solution, I’ve learned, requires cooperation with your neighbors. But there’s no reason to stop there. With some broader teamwork, we could all one day be stronger against the bigger pests plaguing our homes.

Top illustration by Tiffany Jan

Related Reading:

A Comprehensive Guide on How to Handle the Pesky Vermin Invading Your Home

New York City Is Failing Tenants. So They’re Getting Organized

‘I Will Die Here’: A Conversation With My Mom About Her East Village Apartment of 27 Years

The nondescript 2000s residence now channels Belgian minimalism with luxe finishes like plaster and marble.

For architect Francisco Arredondo, principal of North Arrow Studio, there are two types of clients: those who think they know what they want, and those who know what they want. “We like working with the ones that know,” he says. One such was Aditi, who was living in an early-2000s spec house in South Austin. Just Arredondo’s type, she came to him for a renovation with a number of specific goals and decisive design inspiration.

This 2004 Craftsman-style house was “a little bit dull” and didn’t fit with the charm of its neighborhood, says architect Francisco Arredondo.

Photo:

After renting the home for a few years, Aditi fell in love with the neighborhood’s walkability and character, but the house itself left much to be desired. “It didn’t quite fit her lifestyle or the things she values in a home,” Arredondo says. So what did she value, exactly? A connection between interior and exterior spaces, a facade that makes a home relatable to its neighborhood, and plenty of natural light while maintaining privacy.

Aesthetically, Aditi was drawn to the warmth, sophistication, and restrained minimalism of Belgian design—”particularly the work of Axel Vervoordt, Dieter Vander Velpen, and Marie Lecluyse,” she says—which she felt would give her home an overarching European sensibility.

Arredondo lightly reworked the home’s shape to make it “appear less imposing from the street.” In part, this meant rebuilding the carport and front porch. The exterior is now clad in yakisugi, which has an “alligator-like texture to it,” says the architect, and makes it naturally weatherproof.

Photo by Lindsay Brown

Getting the exteriors right was important to Arredondo, too. “We didn’t want to make a big statement,” he says. “It’s very important to us that our work, whether it be new construction or a remodel, fits within the neighborhood.” Whereas before the Austin home had vertical siding in a dull color, now it’s clad in yakisugi, a charred-wood finish that, in tandem with new large windows and doors, makes the exterior feel quiet, warm, and modern.

By expanding the entryway, Arredondo and designer Emily Brown of Emily Lauren Interiors were able to leave more square footage for the kitchen, which felt dated.

Photo:

See the full story on Dwell.com: Before & After: She Renovated Her Austin Home With an Unusually Specific Aesthetic

Related stories:

In the news: An Icelandic wheelchair ramp project sets a new precedent for accessibility, Rocket Co.’s buying spree to control the housing market, L.A.’s newest plan to turn offices into housing, and more.

The City of Los Angeles is planning to turn vacant offices into residences.

Photo by Patrick T. Fallon/AFP via Getty Images

Los Angeles recently approved Adaptive Reuse Ordinance 2.0, an ambitious plan to tackle the housing crisis by turning vacant offices and underused buildings into residential spaces. (ArchDaily)

Dr. Lucy Jones warns that climate-fueled wildfires are now a greater threat to L.A. than earthquakes. With weak enforcement of building codes, the city is dangerously unprepared, she says. Here’s why she thinks residents shouldn’t rely on government action to prepare the next fire. (Dwell)

Top image courtesy of The Oppenheim Group/Roger Davies

Opening this week in Chicago, the National Public Housing Museum wants to reinvigorate our interest in collective well-being by tackling dominant narratives—of crime, poverty, and eventual destruction—head on.

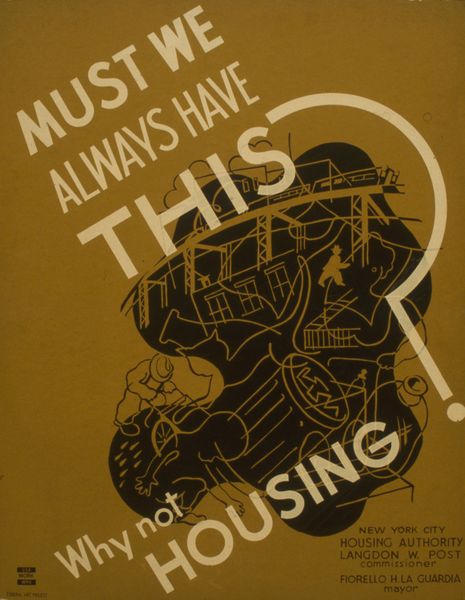

A 1936 advertisement for the New York City Housing Authority depicts the clamor of city life: a jumble of line drawings depict a leaping alley cat, trash can, train, and fire escape. Bold text in a quintessential Art Deco font plastered diagonally across the image reads, “Must we always have this? Why not HOUSING?,” addressing both the energy and desperation of urban life in 1930s America. Funded by the Works Progress Administration, the ad was of a time when the federal government created massive public works projects across America to uplift the poor during the Great Depression.

A 1936 poster promoting planned housing as the solution to a host of inner-city problems shows an inkblot on which elements of inner-city life are drawn.

Photo courtesy Library of Congress

Though that era is now long over, the ad still feels relevant. We’ve reached a record high of unhoused people across the country: new housing construction is slow, rent costs burden more than 50 percent of Americans, and building housing is only getting more expensive. We may have driverless taxis coasting through cities and technology that delivers anything you desire in a matter of hours…but why not housing, indeed?

The advertisement is one of many artifacts on display at the new National Public Housing Museum (NPHM) in Chicago, the country’s only museum devoted to U.S. public housing, which opens April 4. Unlike other types of history museums which seek to keep the past alive, the NPHM is in a unique position because public housing itself isn’t, technically, extinct. People still inhabit public housing developments constructed across the country after the U.S. Congress committed to building public housing in the National Housing Acts of 1935 and 1937. As such, the NPHM is doing something a bit different. They’re not preserving objects and artifacts to encase public housing in amber; instead, the space squarely seeks to reinvigorate our interest in collective well-being by tackling public housing’s dominant narrative—one of crime, poverty, and eventual destruction—head on.

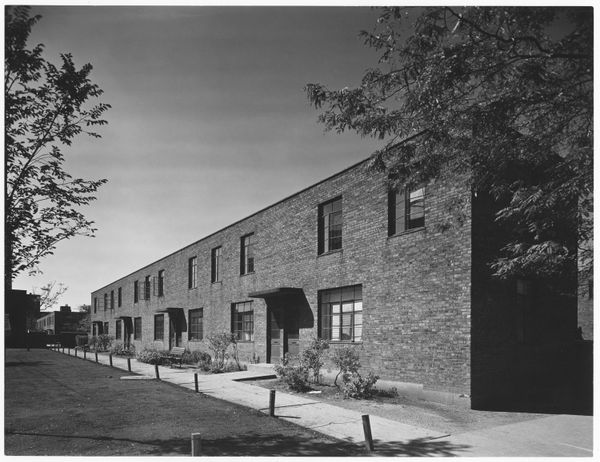

Located in Chicago’s Little Italy neighborhood, the NPHM is housed in the remaining structure that was once part of the Jane Addams Homes—a 1937 low-rise public housing development that was mostly demolished beginning in 2002. According to NPHM executive director Lisa Lee, the building itself is the museum’s biggest artifact, saved by a group of former public housing residents when the City of Chicago embarked on its 1999 Plan for Transformation that got rid of 18,000 public housing units and displaced more than 16,000 people. At that point, it had been the largest net loss of affordable housing in the entire United States, says Lee.

An exterior view of Chicago’s (now mostly demolished) Jane Addams Homes in 1949.

Photo by Hedrich-Blessing Collection/Chicago History Museum/Getty Images

An archival photo shows children playing in fountains and on animal sculptures in the courtyard of the Jane Addams Homes public housing project.

Photo by Hedrich-Blessing Collection/Chicago History Museum/Getty Images

See the full story on Dwell.com: Why We Need the Nation’s First Public Housing Museum

Related stories:

Starting in the 1960s, Archigram, Ant Farm, and Superstudio questioned the very fundamentals of architecture, from its relationship to society to the production of buildings.

As a part of our 25th-anniversary celebration, we’re republishing formative magazine stories from before our website launched. This story previously appeared in Dwell’s July/August 2006 issue.

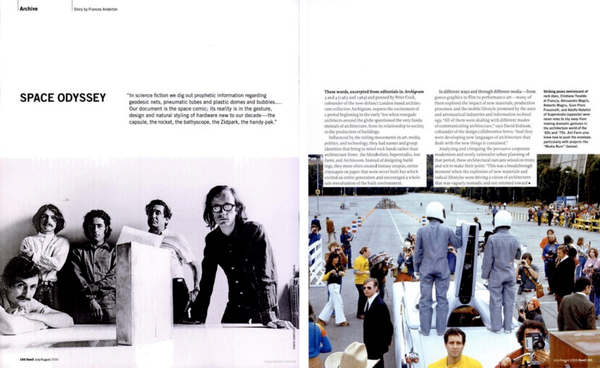

“In science fiction we dig out prophetic information regarding geodesic nets, pneumatic tubes and plastic domes and bubbles….Our document is the space comic; its reality is in the gesture, design and natural styling of hardware new to our decade-the capsule, the rocket, the bathyscope, the Zidpark, the handy-pak.”

These words, excerpted from editorials in Archigram 3 and 4 (1963 and 1964) and penned by Peter Cook, cofounder of the new defunct London-based architecture collective Archigram, express the excitement of a period beginning is the early ’60s when renegade architects around the globe questioned the very fundamentals of architecture, from its relationship to society to the production of buildings.

Influenced by the roiling movements in art, media, politics, and technology, they had names and group identities that bring to mind rock bands rather than architecture firms: the Metabolics, Superstudio, Ant Farm, and Archizoom. Instead of designing buildings, they more often created fantasy utopias, entire cityscapes on paper that were never built but which excited an entire generation and encouraged a wholesale reevaluation of the built environment.

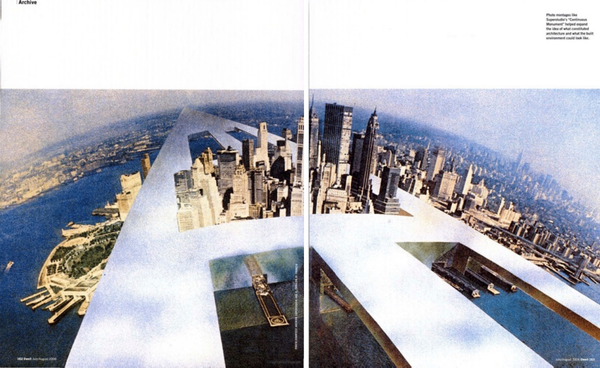

In different ways and through different media—from gonzo graphics to film to performance art—many of them explored the impact of new materials, production processes, and the mobile lifestyle promised by the auto and aeronautical industries and information technology. “All of them were dealing with different modes of communicating architecture,” says David Erdman, cofounder of the design collaborative Servo. “And they were developing new languages of architecture that dealt with the new things it contained.”

Analyzing and critiquing the pervasive corporate modernism and overly rationalist urban planning of that period, these architectural outcasts seized on irony and wit to make their point. “This was a breakthrough moment when the explosion of new materials and radical lifestyles were driving a vision of architecture that was vaguely nomadic and not oriented toward the acquisition of possessions,” explains Craig Hodgetts, architect, professor of architecture, and longtime friend of the Ant Farm group. “The ideal was not the luxury bath we see today but the airplane bathroom.”

These collectives “introduced whimsy and subjectivity and insolence and irony back into architecture,” says Stephen Nowlin, director of the Williamson Gallery at Art Center College of Design in Pasadena. “At the time it was almost sacrilegious that they would do this. But that constructive insolence is one of the most important things you can teach in a design school.” In recent years there’s been a renewed interest in these counter movements with numerous traveling exhibits and academics doing weighty scholarship on their work.

The most influential and productive collective was Archigram, the eldest of the renegade groups. Its members (Peter Cook, Warren Chalk, Dennis Crompton, David Greene, Ron Herron, and Mike Webb) created an astonishing 900 drawings of pen-and-ink and collaged images between 1961 and 1974. The six met in the late ’5os while holding down day jobs at a large construction firm in London. Their nights, however, were spent feverishly drawing imaginary, mobile, temporary environments with electronic age names like the Capsule Home, the Plug-in City, and the Walking City, a megastructure that could plod across the land like a vast robotic animal.

They published their projects, along with essays and poems and the work of other designers they considered to be coconspirators against the establishment, in nine issues of an underground magazine they collaged together called Archigram, first published in May 1961.

See the full story on Dwell.com: From the Archive: How Renegade Architecture Firms Challenged the Status Quo

Set in the San Jacinto Mountains, the ’80s home is surrounded by boulders, trees, and forest trails—and it comes with a guesthouse and a hot tub.

Location: 53590 Jeffery Pine Road, Idyllwild, California

Price: $995,000

Year Built: 1980

Architect: Dennis McGuire

Footprint: 1,429 square feet (3 bedrooms, 2 baths)

Lot Size: 0.57 Acres

From the Agent: “Walk up a winding path of rock steps to experience this architectural gem, designed by Dennis McGuire. It organically rises out of the hillside in company with massive granite boulders, tall pines, cedars, colorful oaks, and Japanese maples. Many decks throughout the property offer sitting places to enjoy morning coffee with the birds, a good book, a conversation with a friend, or time alone breathing in the mountain air. The interior is an airy two-bedroom, one-bath floor plan, with towering ceilings and wood beams throughout. An art studio and a workshop offer space for creative projects of all sorts. Outside, meandering trails and bridges lead to a guest suite designed by the owner with an architectural nod to Corbusier, Eames—and, of course, Thoreau too in its elegant simplicity. The home is nestled in the beautiful Cedar Glen neighborhood, and just outside the door are many forest hikes and the popular Deer Springs Trailhead where adventure awaits.”

Pierre Galant Photography

Pierre Galant Photography

Pierre Galant Photography

See the full story on Dwell.com: This $1M California Cabin Feels Like a Multilevel Tree House

Related stories:

Autonomous’s tiny prefab, which is also solar capable, can be shipped with a suite of ergonomic work-from-home essentials.

Welcome to Prefab Profiles, an ongoing series of interviews with people transforming how we build houses. From prefab tiny houses and modular cabin kits to entire homes ready to ship, their projects represent some of the best ideas in the industry. Do you know a prefab brand that should be on our radar? Get in touch!

Founded in 2015 by CEO Duy Huynh, office furniture company Autonomous took its first foray into smart, tech-enabled designs with the launch of a standing desk on Kickstarter. From there, the company’s offerings expanded to include everything a remote or hybrid worker needs to run a well-equipped work-from-home operation, from ergonomic chairs, to 3D-printed slides, to AI supercomputers. More recently, Autonomous introduced an entire workspace, a plug-and-play backyard office called the WorkPod.

Here, company product manager Brody Slade explains more about the new prefab office and what sets it apart from other workspaces you could put in your backyard.

Autonomous, which started in 2015 by making office furniture, now offers a backyard office called the WorkPod, a tiny modular workspace that can be customized.

Photo courtesy of Autonomous

What does your base model cost and what does that pricing include?

The base model WorkPod is priced at $18,900, offering a gross floor area of 102 square feet. This includes a modular, eco-conscious design, delivered in three large crates with all components and tools for self-installation. We prioritize sustainable materials and efficient design to minimize environmental impact. The price covers the product itself, while shipping, tax, and professional installation are separate due to varying customer locations. We also offer smart-design options like integrated solar panel readiness and energy-efficient lighting.

The design, which emphasizes energy efficiency, includes weather-resistant siding, a single exterior plug to hook up the unit, and six adjustable foundation options to allow for simple installation.

Photo courtesy of Autonomous

What qualities make your prefab stand apart from the rest?

A standard WorkPod interior has a bookshelf and an electrical cabinet; a furnished model ships with a smart desk, ergonomic chair, filing cabinet, anti-fatigue mat, and cable tray.

Photo courtesy of Autonomous

See the full story on Dwell.com: You Can Plug This $19K Backyard Office Into an Outlet

Related stories:

Situated in the heart of the city, the 2,045-square-foot apartment has been refreshed with vibrant hues, terrazzo, and high-end appliances.

Location: Rungestraße 610179 Berlin, Germany

Price: €2,363,000 (approximately $2,550,404 USD)

Year Built: 1933

Renovation Year: 2016

Footprint: 2,045 square feet (3 bedrooms, 3 baths)

From the Agent: “Originally built between 1930 and 1933 by architect Albert Gottheimer, this building embodies expressionist architecture, known for its sculptural forms. Rich with historical detail, the building’s facade is accented by intricate ornamentation and decorative clay figures that flank the entrance. Pilasters nod to the building’s history, while the varying heights, staircase, and entrance portal further emphasize its grand presence.

“Renovated in 2016, this fourth-floor apartment features a cohesive color palette and high-quality materials create a surreal aesthetic. Seamless light gray microcement flooring throughout the apartment is accented by vibrant plastered walls and custom furniture. The entrance features an anthracite wardrobe with a coral seating niche. The heart of the home is the L-shaped living area, awash with sunlight from floor-to-ceiling balcony doors facing south and a window to the west. Terra-cotta and pistachio-green walls bring warmth and a natural vibe, paired with an open Bulthaup kitchen in pale pink.

“An anthracite-colored dressing area leads to the bedroom with a freestanding bathtub and a view over Köllnischer Park. The en-suite bathroom is a mix of blue-green and gold, equipped with Villeroy & Boch ceramics and fittings. A pastel pink children’s room, also overlooking the park, can be divided into two separate bedrooms or studies with a separate shower room located nearby. The sunny balcony off the living room overlooks a quiet courtyard.”

The building is located in Mitte, a central neighborhood in Berlin near the Spree and across from Köllnischer Park.

Photo by Khuong Nguyen

Originally completed in 1933, the building was renovated in 2018. The apartment for sale was renovated in 2016.

Photo by Khuong Nguyen

Photo by Khuong Nguyen

See the full story on Dwell.com: If You Love Pastels, Here’s a Pink and Pistachio Berlin Flat for €2.4M

Related stories: